A closer look at Chinese tea’s application for world heritage status

Editor's Note:

China's traditional tea-making techniques and their associated social practices successfully became UNESCO's latest world intangible cultural heritage on Tuesday, increasing the number of world intangible cultural heritages in China to 43.

Tea is ubiquitous in Chinese people's daily life and has also influenced the lives of people around the world through the Silk Road. It's a pleasure to see the successful application of this ancient art.

In this series on Chinese tea culture, the Global Times shares with readers what makes this intangible cultural heritage so special. Following the first two installments about the successful application and the role of tea in international exchanges, this final installment explores the application process itself and how China's experience with culture conservation made the inclusion possible.

"I declare the decision adopted. Congratulations, China."

After the UNESCO jury in Morocco announced that Chinese tea-making techniques and their associated social practices had been approved for the World Intangible Cultural Heritage List on Tuesday, the application team jumped for joy and hugged one another as the sound of applause and exalted cheers echoed throughout the meeting room.

Due to recent nationwide COVID-19 flare-ups, most members of the team could not attend the 17th session of the UNESCO Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage held in the Kingdom of Morocco, so they had to watch the gala online.

"We were quite confident about the application this time," Wang Fuzhou, director of the China Intangible Cultural Heritage Protection Center and a member of the application team, told the Global Times.

He explained that they selected Chinese tea for this World Heritage application because of its wide distribution, rich heritage in traditional techniques as well as its glorious history and high reputation around the world.

One of the people holding up this reputation is Yang Feng, an intangible culture inheritor of Chinese white tea in East China's Fujian Province who once displayed China's splendid tea techniques at the G20 summit held in Hangzhou, East China's Zhejiang Province in 2016.

"Chinese tea is famous around the world. I remember that the leaders of the world's major economies gave a big thumbs up to our tea after tasting some at the summit. It was a really terrific experience," Yang told the Global Times.

Heavy responsibility

Compared with the previous intangible cultural heritage declaration projects, Wang said the latest application is the "largest" they have done as it consists of 44 smaller projects from 15 places around China.

One of the top 10 renowned teas, China West Lake Longjing tea was included in the application.

Fan Shenghua, a provincial-level inheritor of the art of frying Longjing leaves who participated in the project, told the Global Times that he and many tea-making inheritors and producers felt exalted after hearing the good news, but at the same time "the inclusion means we shoulder a heavier responsibility and must perform better to inherit this tradition."

Having been frying Longjing leaves for over 48 years, the veteran tea-maker's hands are covered in calluses from rubbing his thick palms against the high-temperature frying pan he uses to fry the fragrant leaves used to make West Lake Longjing tea.

Fan said one catty (600 grams) of dried tea can be made from frying 20 pots of leaves, with each pot containing an average of 2.5-catties of fresh leaves. During their peak period, five to six catties of dry tea can be roasted a day if they go without sleeping day or night.

To "pass down the tea-frying craft left by our ancestors," Fan has been teaching how to make West Lake Longjing tea at schools and vocational schools since 2015.

"Frying tea requires patience, which is what I often emphasize with young people," he said.

Creativity and technology

Believing that protecting intangible cultural heritage is a task for all of humanity, China joined the Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2004.

Wang said that over the past few decades, China has developed a set of intangible cultural heritage systems with Chinese characteristics that have won the appreciation of UNESCO and many other countries.

He pointed out that many intangible cultural heritages around the world have only survived by relying on government subsidies, but in China they have survived and even thrived because of the creativity of its people and the support of advanced technology.

For instance, a smash hit TV drama A Dream of Splendor introduced the tea technique chabaixi to Chinese audiences. Chabaixi is a unique technique popular during the Song Dynasty (960-1279) in which the tea master uses tea foam to draw patterns on the surface of the tea. A drink which was inspired from the drama later flew off the shelves and set a record sales volume of 300,000 cups nationwide in a day.

Livestreaming is also a popular platform in spreading traditional Chinese culture. Fan said he has made a lot of new tea-making friends through livestreaming.

With the advent of the digital age, Wang noted that digital protection and promotion of intangible cultural heritage has become a trend.

State media outlet CCTV reported that 12 digital collections inspired by Dragon Boat Festival symbols went on sale online in June.

A total of 52,277 people viewed the digital collection within the first 24 hours of it going online on June 1, and 24,000 copies were sold in less than three minutes after sales began on June 2.

Ningbo seabird project seeks international volunteers

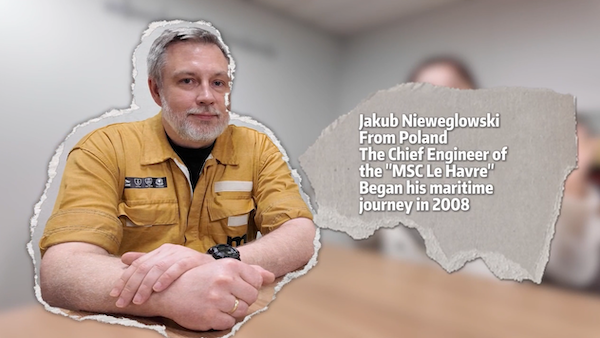

Ningbo seabird project seeks international volunteers  Jakub's journey: From shipyard to sea

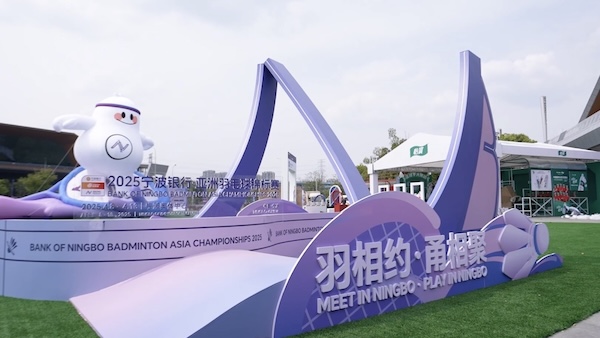

Jakub's journey: From shipyard to sea  Badminton Asia COO applauds Ningbo

Badminton Asia COO applauds Ningbo